30 Dec Word of Wisdom #7a: Equitable Student Participation – Part One

To know what students do and do not yet understand, you need each student to respond in some way to questions you ask.

Q AND A – A VALUABLE TEACHER TOOL

The question-and-answer format is a valuable teacher tool. It allows us to check students’ understanding of what they have learned and to probe their thoughts on problem solving. But only if we can limit/squash/dis-encourage student call-outs. The goal is to give every student a voice and to sample the thinking of all students. This lets the teacher know if the instruction has been successful – or if reteaching is needed. But the over-participation of some students and the silence of others often leaves us with a blurred picture of student understanding. How can you bring this picture into focus?

THE RESPONDING 10% TO 20% – AND THE MISSING 80% TO 90%

But have you noticed that in just about every class there are some students who believe it is their God-given right to call out an answer every question the teacher asks? You’ve probably had some of these in your own classes. I know I have. Indeed, sometimes I didn’t even finish a question before an answer exploded out of the same one or few mouths. Such responses are both encouraging (Yes – some students are getting it!) and frustrating (But – I wonder if the others are…?).

Some teachers refuse to accept student call-outs and adhere to the protocol of Raise your hand and wait to be called on. But there is a problem there. Suppose I am a student in your classroom and do not want to be called on? All I have to do is never raise my hand. And if I do raise my hand repeatedly and am seldom or never called on, I may feel a bit like Linus in the Peanuts cartoon below.

Typically, again it is the same few students who continually raise their hands – and get called on.

Now the thing about the same 10% to 20% of the class who continually participate – either by call out or raised hand – is that their typically correct answers positively reinforce us and make us feel like good teachers. And that is a good feeling. But feeling good is not our goal. We are not getting feedback on the other 80% to 90% of our students, and we cannot assume that those nonparticipating students are understanding as well as the participating ones. In fact, that’ probably the reason their hands are not up.

Note: For additional ideas for the elementary classroom to discourage callouts, see http://thepinspiredteacher.com/2017/05/16/9-guaranteed-ways-stop-students-blurting/ )

True Story #1 – “If Alene Understands…”

I think about a statistics professor I once had in graduate school who obviously understood this principle – and also understood that I was his weakest student in that course. One day a fellow student posed a question in class, and the professor turned to him and announced in amazement, “You don’t understand that? Even Alene understands that.” Now we all laughed, including me, but the truth was that if Professor Sandler had explained a statistical concept so that I understood it, he knew he had surely communicated it with the rest of the class.

THREE STEPS TO CHECK THE UNDERSTANDING OF ALL STUDENTS

So does this mean teachers should just check the understanding of the weaker students? NO! The goal is to give every student a voice and to sample the thinking of all students. Allowing student call-out does not do this. Neither does calling only on students with raised hands. So how can a teacher do this?

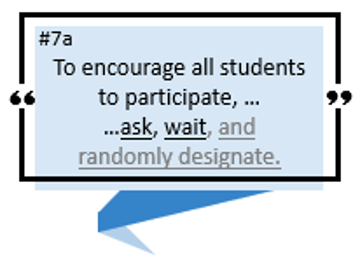

One way is with the three steps of (1) ASK, (2) WAIT, and (3) RANDOMLY DESIGNATE.

STEP ONE: Ask the question of all students – no designation yet of who will be called on to answer. (Note: One way to prevent call-outs is to have students assume a “thinking position” before the question is asked. This involves a finger over the lips, which inhibits speaking. (Lesson I once learned from a special education teacher: Make it impossible for a student to do both the undesired and desired behavior at the same time.)

STEP TWO: Wait… at least three seconds. Studies show that typical teacher wait time between asking a question and expecting a response is less than a second. They also show that giving students three to five seconds to think before answering results in (a) more students volunteering to respond, (b) higher order thinking in students’ answers, and (c) greater learning gains (Ingram & Elliott, 2016).

STEP THREE: Randomly designate who is to respond. The challenges here are (a) truly randomly designating students to respond, (b) at the same time making sure every student is called on, and (3) keeping track of who has and has not been called on. How to do all three of these? One way is with a technique called equity cards that will be discussed in next week’s blog.

KEYS FOR SUCCESSFUL “ASK” AND “WAIT”

For now, let’s concentrate on steps one and two – ASK and WAIT.

ASK: Consider the following scenario. You are a student, and your teacher is beginning a Q & A review session over the unit you are finishing. He says, “There are three key ideas you should be able to discuss from our lessons this past week. Sam, can you give us one of these?” Now unless your name is Sam, you have likely just said a silent mental “Whew!” of thankfulness. How engaged are you in thinking about the question at hand? Not very.

But if instead your teacher said, ““There are three key ideas you should be able to discuss from our lessons this past week. Before anyone answers, everyone take the next five seconds to think how you would state these ideas, and then I’ll call on someone.”

So – asking the question before you ever call a student’s name helps keep all students focused.

WAIT: Three-fifths of a second is not much time, yet that is the average teacher wait-time in U.S. schools. Think I’m exaggerating? Use your phone to audio record your next Q & A session with your students and check how “average” your own wait time is. So what is the optimum wait time? Some studies indicate 3 seconds; others, 5 seconds. Giving students those extra seconds to think will result in more students willing to respond and in higher-order thinking in their responses. Both of these are good things! But you’ll have to train yourself to allow wait time.

True Story #2 – Learning to Wait

When I first learned about wait time and discovered I was indeed quite “average,” I asked my student to help train me. I told them I had learned that if I would give them more time to think when I asked a question, they would get more right answer. Would they like to get more right answers? Yes. So would they help me learn to give them time to think? Yes.

Together we watched the second hand on the clock. We counted “thousand-one, thousand-two thousand-three” several times to get the feel of three seconds. I explained I’d made a card (8.5 x 11 cardstock) with big red letters TIME on it. For the next several days I would ask different students to help me. If I did not allow at least three seconds, the designated student was to hold up the card to remind me. They agreed with enthusiasm. It took a little over three weeks to train me to allow at least three minutes of think time. Everybody got a chance to “remind the teacher.” And yes, they did get more right answers.

Note: For more on wait time, check out the first part of the video at https://study.com/academy/lesson/non-verbal-and-verbal-communication-in-the-classroom.html. (No need to sign up for the course…)

Until next week when we look at a way to equitably distribute opportunities to participate – may you experience success in all your academic endeavors!

Alene

Ingram, J., & Elliot, V. (2016). A critical analysis of the role of wait time in classroom interactions and the effects on student and teacher interactional behaviours, Cambridge Journal of Education, 46(1), pp. 37-53.